The Highcloaks

We walked in the darkness of the canyon for what seemed like forever. With each step in that abyss, I began to wonder if I’d ever see light again. Emrys didn’t say much by way of comfort. His answers were short whenever I asked how much farther it would be until we reached the end of the valley. A simple, “Keep walkin’, son.” Perhaps it was that he did not truly know himself.

Finally, we made it. The path opened to a wide landscape of rolling hills. The sun was just rising over the horizon, and the dew on the tall grass shimmered in the new light. We stood at the mouth of the canyon for a moment and took it in. Birds were waking, their song melting the horrors of the valley into something like a distant memory. In the distance, deer grazed, and beyond them faint trails of smoke rose straight and thin, like chimneys on a cool autumn morning.

A town.

Emrys said nothing. He shaded his eyes with one hand and stared ahead as though listening for something the earth might say back.

The crown gnawed at my arms the way a thought gnaws at the mind: a steady bite in the same old place. The memory of the Voice still trembled in my bones—Child, stand up. Walk.—but the tremor had become an ache now, and ache reminded me of hunger.

And once I remembered hunger, it ruled me.

“I have to find food,” I muttered, more to myself than to Emrys.

“Aye,” he said. “Let’s go.”

We walked on.

By midday we stopped to rest. It seemed that no matter how far we went, the town never drew closer.

We found shade beneath a cluster of trees beside the path. Emrys produced a long pipe from somewhere, and soon the smell of burning tobacco mixed with the scent of grass and bark. Across the path, the same wide field stretched away, the deer now gone. Birds replaced them, darting from tree to tree. Sometimes they mistook Emrys for a trunk and landed on his shoulder until he shifted and sent them fluttering away.

I think back to that moment often. I cannot recall a time I felt more at peace. Even the crown seemed lighter. We lingered long enough that I drifted into a light sleep.

I woke to the sound of footsteps—many, heavy, and close. Voices followed. I sat up and saw a caravan of travelers coming along the path toward the same town.

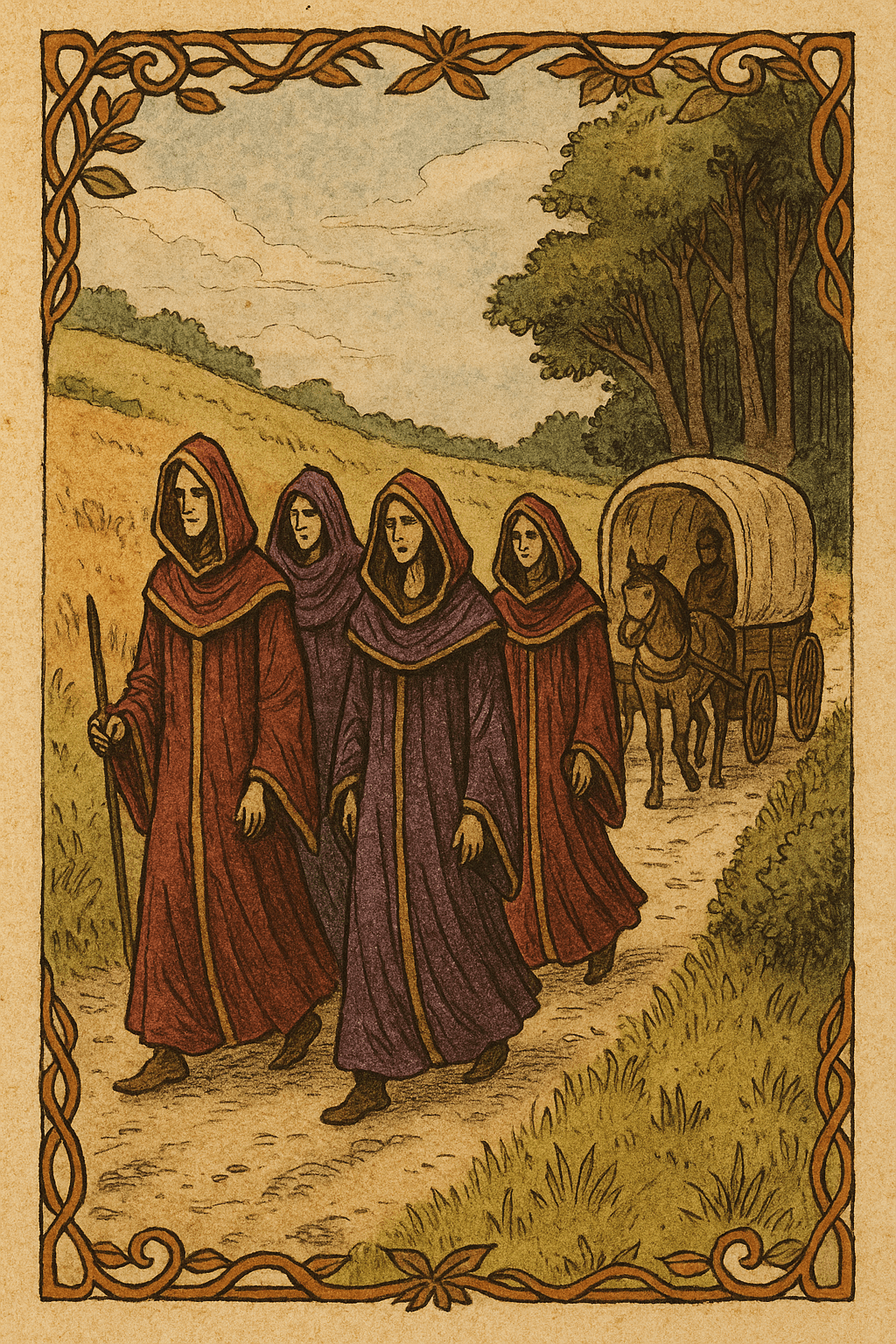

They were tall, slender people, some so tall they ducked beneath the branches. Their robes shimmered in shades of deep red and purple, stitched with threads of gold.

I glanced at Emrys. He seemed unbothered, puffing along. And then I remembered: the King’s robe. These were beautiful, yes, but they looked like copies—imitations of something greater.

“Emrys, are they royalty?” I asked. “Their clothes look like the King’s.”

The band drew near.

Emrys looked at me, then at them, and chuckled. “Aye, those are the Highcloaks. They want so badly to be wee kings. But it’ll take more than gaudy cloth to make real royalty.”

I looked back at them. Now I noticed how ridiculous they seemed. From a distance their clothing had shimmered; up close, the seams were crooked. They walked with their chests puffed out, their faces stiff with seriousness, as if every step were a noble sacrifice. It all looked exaggerated. Forced.

The Highcloaks slowed as they drew near, tall forms swaying in their crimson and purple. Gold threads caught the light. They never looked at us directly, but always out of the corner of their eyes—as though turning their heads fully toward us would be beneath them.

“Brother,” one finally said, bowing his head toward me with practiced sincerity. “You look weary. Come with us, and you will find rest.”

Another’s eyes fell on the crown in my arms. He flinched. “But what is this? Obscene. Such things should not be carried in the open.”

Without thinking, I hid it behind my back. I was ashamed, though part of me felt I had earned the crown. Then I remembered how I had taken it, and who it belonged to. The shame deepened. “It… it’s not obscene,” I stammered.

“Not obscene?” the first said, pity softening his features. “That weight is shame, not honor. Look at us—clothed in the likeness of the King, as all who love Him should be. That thing you clutch mars you. Set it down, and be clothed as we are.”

Before I could answer, Emrys spoke, his voice quiet, almost bored. “Aye, fine cloth. But the King’s no tailor. He clothes hearts, no’ backs.”

The Highcloaks glanced at him briefly, then turned back to me as though he hadn’t spoken at all.

“You must be hungry,” said another. Her voice was musical, her eyes kind. “Walk with us. We go to the town ahead—Sunderfell. There is food, shelter, company. But only if you put aside that shadow.”

My stomach knotted. Food. Shelter. Company. The very things I longed for.

One leaned closer, lowering his voice as though sharing a secret. “Why do you follow him?” He jerked his chin at Emrys. “His kind speak riddles, pretending to be the King’s men. But the King has no need of wanderers.”

The others murmured assent.

“Yes. He twists truth.”

“He binds you to your shame.”

“He would leave you hungry forever.”

I looked at Emrys. He puffed his pipe in silence, smoke curling upward. He did not argue.

The Highcloaks pressed closer. “Come with us. Leave him. We will take you to Sunderfell. There you will belong.” They gestured toward their ornate horse and carriage. “You must be tired. Come and rest.”

My arms trembled around the crown. My hunger roared. My whole body ached with exhaustion.

Emrys met my eyes at last. Smoke drifted from his lips as he said, “Aye, lad. Ye can go. I’ll no’ chain ye to my side. But ken this: not every fire that warms ye comes from the King’s hearth. Ye’ll find out soon enough.”

I hated the calm in his voice. I hated that he wouldn’t fight me.

“I’m sorry, Emrys. I don’t think my legs will carry me much farther. I’ll go with them for now,” I said, my throat dry.

The Highcloaks smiled. Their warmth toward me deepened, but their faces hardened when they looked at Emrys.

“Shame,” one said. “There’s only room for one, old man.”

A woman snickered.

“I pray the King have mercy on you,” the leader said flatly.

Their contempt was thick now, unmasked. Yet they treated me with all the gentleness in the world, guiding me toward the carriage, offering me a place among them.

I glanced back once. Emrys had not moved. Smoke curled from his pipe, his eyes steady on me. Then I blinked—he was gone. Only the faint curl of his last smoke lingered in the air.

I looked away and tried to force myself to sleep.

Leave a comment